Four years ago, Pure Storage pioneered fast object storage with the launch of its FlashBlade system. Today fast object storage is ready to go mainstream, with six vendors touting the technology.

Object storage has been stuck in a low performance, mass data store limbo since the first content-addressed system (CAS) was devised by Paul Carpentier and Jan van Riel at FilePool in 1998. EMC bought FilePool in 2001 and based its Centera object storage system on the technology it acquired.

Various startups including Amplidata, Bycast, CleverSafe, Cloudian, Scality developed object storage systems. Some were bought by mainstream suppliers as the technology gained traction For instance, HGST bought Amplidata, NetApp bought Bycast and IBM bought CleverSafe.

Objects became the third pillar of data storage, alongside block and file. It was seen as ideal for unstructured data that didn’t fit in the highly structured database world of block storage or the less highly structured file world. Object storage strengths include scalability, ability to deal with variably-sized lumps of data, and metadata tagging.

Object storage systems typically used disk storage and scale-out nodes. They did not take all-flash hardware on board until Pure Storage rewrote the rules with FlashBlade in 2016. Since then only one other major object storage supplier – NetApp with its StorageGRID – has focused on all-flash object storage. This is a conservative side of the storage industry.

Commonsense is one reason for industry caution. Disk storage is cheaper than flash and object storage data typically does not require low latency, high-performance access. But this is changing, with applications such machine learning requiring fast access to millions of pieces of data. Object storage can now be used for this kind of application because of:

- Standardisation on S3 object interface across object storage vendors,

- Addition of file access gateways to object storage,

- Use of all-flash hardware,

- Radically improved object storage software stacks,

- Emergence of machine learning at edge computing locations.

A look at products from MinIO, OpenIO, NetApp, Pure Storage, Scality and Stellus shows how object storage technology is changing.

Minio

MinIO develops open source object storage software that executes very quickly. It has run numerous benchmarks, as we have covered in a number of articles. For instance:

- MinIO is faster than Hadoop; farewell, NAS and SA,

- MinIO fires fresh salvo in object storage speed wars,

- Traditional file and block storage vendors are toast – MinIO.

MinIO has demonstrated its software running in the AWS cloud, delivering more than 1.4Tbit/s read bandwidth using NVMe SSDs. It has added a NAS gateway that is used by suppliers such as Infinidat. Other suppliers view MinIO in a gateway sense too. For example, VMware is considering using MinIO software to provision storage to containers in Kubernetes pods, and Nutanix’s Bucket object storage uses a MinIO S3 adapter.

All this amounts to MinIO object storage being widely used because it is fast, readily available, and has effective S3, NFS and SMB protocol converters.

OpenIO

OpenIO was the first object storage supplier to demonstrate it could write data faster than 1Tbit/sec. It reached 1.372Tbit/s (171.5GB/sec) from an object store implemented across 350 servers. This is faster than Hitachi Vantara’s high-end VSP 5500‘s 148GB/sec but slower than Dell EMC’s PowerMax 8000 with its 350GB/sec.

The OpenIO system used an SSD per server for metadata and disk drives for ordinary object data, with a 10Gbit/s Ethernet network. It says its data layer, metadata layer and S3 access layer all scale linearly and it has workload balancing technology to pre-empt hot spots – choke points – occurring.

Laurent Denel, CEO and co-founder of OpenIO, said: “We designed an efficient solution, capable of being used as primary storage for video streaming… or to serve increasingly large datasets for big data use cases.”

NetApp StorageGRID

NetApp launched the all-flash StoregeGRID SGF6024 in October 2019. The system is designed for workloads that need high concurrent access rates to many small objects.

It stores 368.6TB of raw data in its 3U chassis and there is a lot of CPU horsepower, with a 1U compute controller and 2U dual-controller storage shelf (E-Series EF570 array).

Duncan Moore, head of NetApp’s StorageGRID software group, said the software stack has been tweaked and there is scope for more improvement. Such efficiency was not needed before as the software had the luxury of operating in disk seek time periods.

Pure Storage FlashBlade

FlashBlade was a groundbreaking system when it launched in 2016 and it still is. The distributed object store system uses proprietary hardware and flash drives and was given file access support from the get-go, with NFS v3. It now supports CIFS and S3, and offers up to 85GB/sec performance.

Pure Storage markets FlashBlade for AI, machine learning and real-time analytics applications. The company also touts the system as the means to handle unstructured data in network-attached storage (NAS), with FlashBlade wrapping a NAS access layer around its object heart.

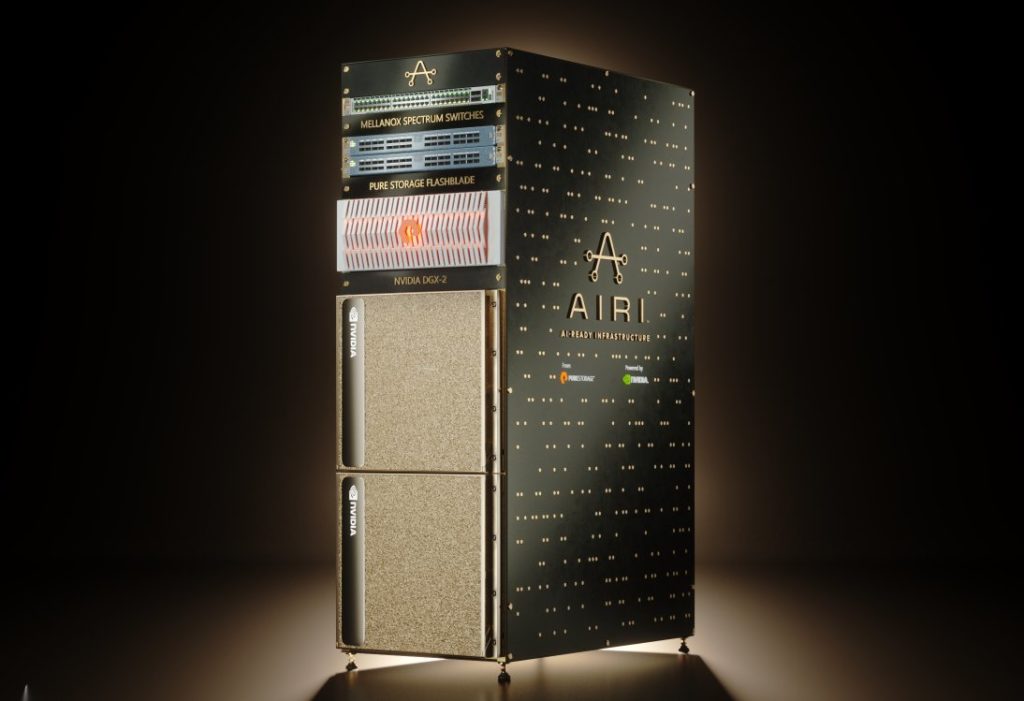

The AIRI AI system from Pure, with Nvidia GPUs, uses FlashBlade as its storage layer component.

Scality

Scality is a classic object storage supplier which has seen an opening in edge computing locations.

The company thinks object storage on flash will be selected for edge applications that capture large data streams from mobile, IoT and other connected devices; logs, sensor and device streaming data, vehicle drive data, image and video media data.

The data is used by and needed for local, real-time computation and Scality supports Azure Edge for this.

Stellus

Stellus Technologies, which came out of stealth last week, provides a scale-out, high-performance file storage system wrapped around an all-flash, key:value storage (KV store) software scheme. Key:value stores are object storage without any metadata apart from the object’s key (identifier).

An object store contains an object, its identifier (content address or key) and metadata describing the object data’s attributes and aspects of its content. Object stores can be indexed and searched using this metadata. KV stores can only be searched on the key.

Typically KV Stores contain small amounts of data while object stores contain petabytes. Stellus gets over this limitation by having many KV stores – up to 4 per SSD, many SSDs and many nodes.

The multiple KV stores per drive and an internal NVMe over Fabrics access scheme provides high performance using RDMA and parallel access. This is at least as fast as all-flash filers and certainly faster than disk-based filers, Stellus claims.

Net:net

There are two main ways of accelerating object storage. One is to use flash hardware with a tuned software stack, as exemplified by NetApp and Pure Storage. The other is to use tuned software, with MinIO and OpenIO following this path.

Stellus combines the two approaches, using flash hardware and a new software stack based in key:value stores rather than full-blown object storage.

Scality sees an opening for all-flash object storage but has no specific version of its RING software to take advantage of it – yet. Blocks & Files suggests that Scality will develop a cut-down and tuned version for edge flash object opportunities, in conjunction with an edge hardware system supplier.

We think that other object storage suppliers, such as Cloudian, Dell EMC (ECS), Hitachi Vantara, IBM and Quantum, will conclude they need to develop flash object stores with tuned software. They can see the possibilites of QLC flash lowering all-flash costs and the object software speed advances made by MinIO, OpenIO and Stellus.