Analysis: As mainstream storage suppliers have adopted and acquired HCI, NVMeoF, and object storage technologies and others, a set of startups have found themselves in a well-funded and long-life state in which they appear to have no short-term need of an IPO or acquisition – contravening conventional financial mores.

They appear in no danger of failing and are examples of companies defying typical startup wisdom that you need to IPO or get acquired within six years or so after receiving the first venture capital investment.

According to Statista, in 2020, VC-backed companies went public approximately 5.3 years after securing their first VC investment.

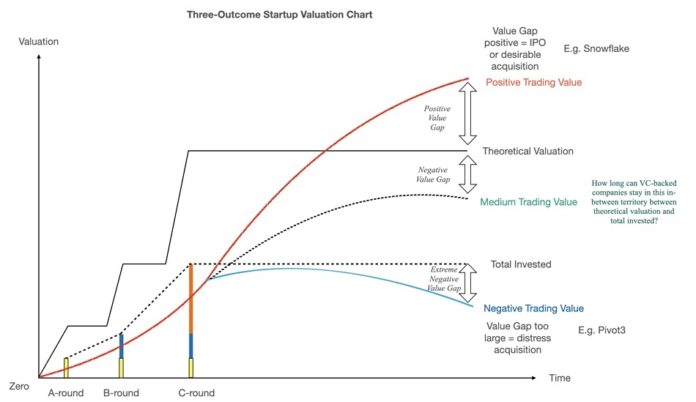

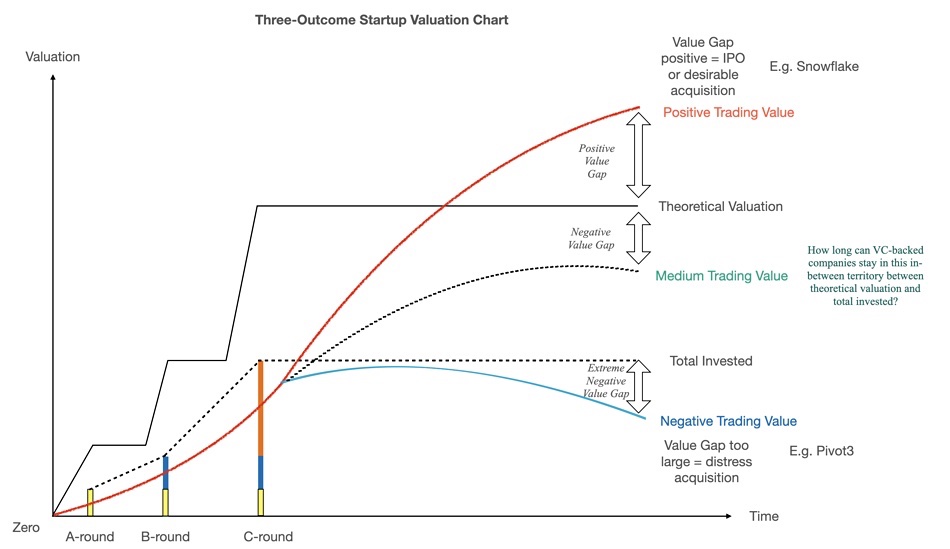

Let’s look at three possible outcomes for a startup:

- IPO or positive acquisition – for example Snowflake IPO and Cleversafe acquisition.

- Crash, burn or distress acquisition – eg Pivot3.

- In-between state – for example Panasas and many others.

Above, we have devised a startup progress chart with these three possible outcomes plotted.

Chart explainer

The chart puts startups’ progress in a time versus valuation 2D space. The coloured bars are venture capital (VC) funding rounds and we show, as an example, A-, B- and C-rounds with the height of the bar representing total funding so far. The dashed line represents the total VC funds invested in the startup.

The solid line above this represents the company’s VC-calculated valuation at reach round. The red curve represents a theoretical startup’s progress as its trading value – what an acquirer would pay grows over time, surpasses the total invested amount and then rises further, past the theoretical valuation, putting the company in IPO territory as it approachers and passes that valuation. It has a positive trading value gap in our chart’s terminology.

At this point the VCs would get a good return on their investment if the company had an IPO or was acquired.

The blue line shows an under-performing startup whose trading value never rises above or drops below the total amount invested. There is an extreme negative value gap between the two and the VCs exit the company because it crashes – Coho Data and Tintri for example – or gets acquired as a distress purchase before bankruptcy, with Pivot3 as our cited example.

The middle, dotted, medium trading value line represents companies which don’t attain a trading value above their theoretical valuation but neither does their trading value drop below the total invested, giving the VCs hope that they will be able to achieve a good exit, eventually. We say these inbetweener companies have a negative value gap.

VC theoretical valuations

How are VC valuations worked out? Kasten co-founder Niraj Tolia said “There is the theory that valuations should be based on discounted cash flows in the future but usually the reality is a lot more imprecise.”

Sometimes sane valuations for later stage companies will be based on “forward multiples” of, say, a multiple of the next 12 months projected revenue. Harder to do for an earlier stage company and that will then look at TAM and other market comps, founder histories, potential for exit and more.

“And, finally, there are some valuations that are simply hard to justify from the outside looking in. Might be a hot deal that got competitive and all metrics got thrown out of the window (like last year in a LOT of deals). Sometimes it’s what a founder can command based on a large vision.

“Basically, more art than science.”

Inbetweeners

Such companies can’t raise any additional funding and they either motor along in good medium trading value shape with adequate profitability, limp along with low profitability unless and until their VC backers want to exit with a closure or firesale or just cash burn themselves out of money. Perhaps a good example of this negative trading value state is Pivot3, a hyper-converged startup. It was started up in 2003 and took in a lot of money – $247 million across 12 funding events. Seventeen years after being founded it was bought by Quantum for $8.9 million, meaning a loss of $238 million for its backers.

What happened? The mainstream vendors built or acquired their HCI products and Pivot3 was not acquired. It then found that its effective addressable market shrank because the big beasts – Cisco (Springpath), Dell EMC (VxRAIL, vSAN), HPE (Nimble dHCI, Simplivity), NetApp (Elements HCI) and Nutanix – were roaming around and mopping up customers. Pivot3’s growth tailed off, faltered and stopped.

The COVID pandemic didn’t help and Pivot3’s board decided to get out of the HCI business.

Inbetweener status can be attained by any startup, whatever its funding amount. The tension between the aims of the VC backers (and most probably part-owners) meaning a good exit, and what the company’s executive leadership can deliver in terms of trading value is greatest in the well-funded in-betweeners. There is simply more VC money at risk.

Identifying inbetweeners

How might we identify long-life, well-funded inbetweener storage companies? Try this: we’ll look for VC-backed, $100 million-plus funded, post-startup suppliers, meaning more than five years since being funded, who have not significantly pivoted in the last few years. Here’s a starting list of $100 million-plus funded, “inbetweener” suppliers:

- Databricks – $3.6 billion

- Fivetran – $730 million

- Cohesity – $600 million (IPO filed)

- Rubrik – $552 million plus

- OwnBackup – $507 million

- Druva – $475 million

- Dremio – $410 million

- Qumulo – $351 million

- Redis Labs – $347 million

- Infinidat – $325 million

- Silk – $313 million

- Pensando – $313 million

- Fungible – $311 million

- Wasabi – $284 million

- Firebolt – $269 million

- SingleStore – $264 million

- VAST Data – $263 million

- Yellowbrick Data – $248 million

- Clumio – $186 million

- Cloudian – $173 million

- Scality – $172 million

- Nasuni – $167 million

- Spin Memory – $166 million

- Virtana – $165 million

- Panasas – $155 Million

- Liqid – $150 million

- WEKA – $140 million

- Egnyte – $138 million

- MinIO – $126 million

- Delphix – $124 million

- Kyligence – $118 million

- Datameer – $117 million

- Pliops – $115 million

- Pavilion Data Systems – $107 million

- ExaGrid – $107 million

- Scale Computing – $104 million

- Elastic Search – $104 million

- GoodData – $101 million

- CTERA – $100 million

Now we’ll separate out those that are seven years old or older, classifying them as startups still:

- Databricks – $3.6 billion and in 9th year

- Fivetran – $730 million and in 10th year

- Cohesity – $600 million and in 9th year (IPO filed)

- Rubrik – $552 million+ and in 8th year

- OwnBackup – $507 million and in 10th year

- Druva – $475 million and in 14th year

- Qumulo – $351 million and in 10th year

- Redis Labs – $347 million and in 11th year

- Infinidat – $325 million and in 12th year

- Silk – $313 million and in 14th year (including Kaminario period)

- SingleStore – $264 million and in 11th year

- Yellowbrick Data – $248 million and in eighth year

- Cloudian – $173 million and in 11th year

- Scality – $172 million and in 13th year

- Nasuni – $167 million and in 14th year

- Spin Memory – $166 million and in 15th year

- Virtana – $165 million and in 14th year (including Virtual Instruments period)

- Panasas – $155 million and in 22nd year

- WEKA – $140 million and in 9th year

- Egnyte – $138 million and in 15th year

- MinIO – $126 million and in 8th year

- Delphix – $124 million and in 14th year

- Nantero – $120 million and in 10th year

- Datameer – $117 million and in 13th year

- Pavilion Data Systems – $107 million and in 8th year

- ExaGrid – $107 million and in 15th year

- Scale Computing – $104 million and in 15th year

- Elastic Search – $104 million and in 10th year

- GoodData – $101 million and in 15th year

- CTERA – $100 million and in 14th year

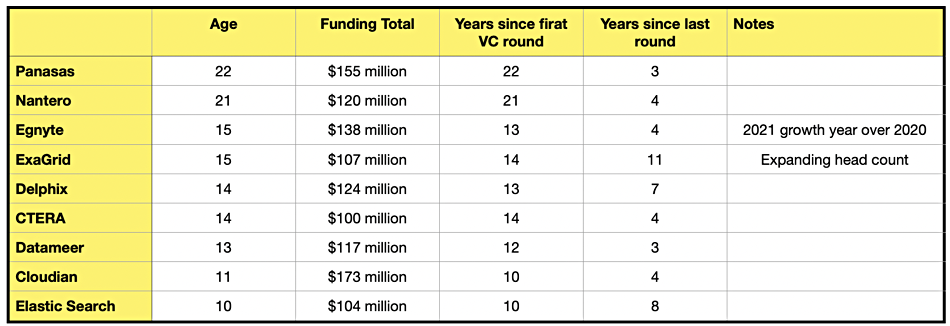

This gives 30 inbetweeener companies. Let’s find out the longest-lived and best-funded ones by putting them in age order, add in the time since the last funding event, and strike out companies less than ten years old, or with two years or less since their last round.

Extreme inbetweeners

We now have nine extreme “inbetweener” companies who are ten years or more old, have $100 million or more in funding, it is ten years or more since their first VC round, and their last funding round was three or more years ago. If asked, all would say they are growing and in good shape. None of them are closing offices or laying off staff. They exhibit no signs of financial stress as far as we can see. Indeed some are visibly and publicly growing, such as Egnyte and ExaGrid.

The current storage market supports – indeed seems to welcome – these players, as they continue to develop and grow their businesses. Long may it continue and let’s hope that their VC backers find some way to crystallise their investments without the company getting into dire straits. There needs to be, we might say, some way for the holdings of the relatively short-termist VC investors to be turned into the holdings of more, benevolent and long-term investors.

Perhaps a long-term view private equity acquisition, meaning not a slash-and-burn reorganising one, is one possible good outcome.