A claim that Optane cells can’t be immediately read because they need to cool after being written has been rebuffed by Intel, but it declined to comment on suggestions contractual restrictions hindered Optane’s adoption by third parties.

The suggested delayed read time cell cooling issue emerged after talking to sources who were testing early 3D XPoint technology, and who had in turn spoken with both Micron and Intel Optane product managers and engineers.

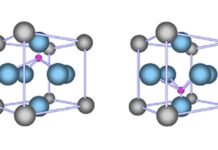

Optane is Intel’s 3D XPoint technology based on phase-change memory cells. The chips were manufactured by Micron in its Lehi fab, until Micron pulled the plug and walked away from 3D XPoint sales, marketing and manufacturing.

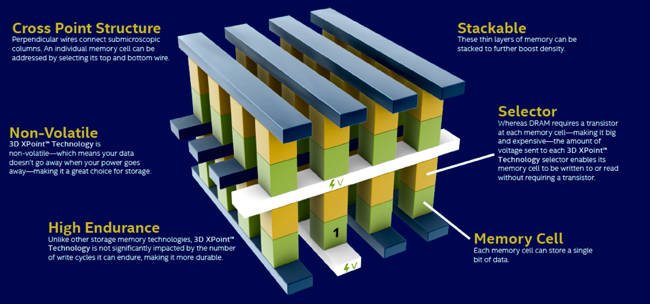

The Intel technology pitch around Optane was that it is cheaper than DRAM but not much slower, while being costlier than NAND but much faster. However, it has struggled to find its niche in the market and a new reason has been identified/suggested for that: the phase change memory cell inside it needs to be heated during the write process and has to cool down afterwards. That means content, once written, can’t be immediately read.

Therefore, Intel had to add DRAM cache to an Optane DIMM/SSD to fix the issue, raising its cost and complexity and making its price/performance ratio increasingly problematic.

Intel, via a spokesperson, said “The assertion that Optane 3D XPoint memory needs to cool down after content has been written is incorrect. Optane memory can be read immediately after it has been written, and this does not drive any special DRAM caching circuitry.”

The reason for the DRAM caching was due to the DRAM-Optane speed difference, according to Intel. “The access latency of Optane 3D XPoint memory is inherently longer than DRAM and to mitigate this impact, Optane is utilised in ‘Memory Mode’. In this mode, a smaller set of DRAM DIMMs are configured as a cache for the larger Optane memory space. The net performance, at a solution level, is 90–100 per cent of the performance of DRAM-only implementation.”

Legal restrictions

We also heard that lawyers protecting Intel and Micron commercial interests put obstacles in the way of third parties needing to talk to their engineers and product people when wanting to use 3D XPoint technology in their own systems. One person told us his people could talk to Micron engineers about 3D XPoint but couldn’t tell Intel they were talking to Micron. They could also talk to Intel XPoint engineers but couldn’t tell Micron about that.

That meant that (a) they couldn’t talk to the Intel and Micron engineers in one room at the same time, and (b) they received mixed messages. For example, Intel product managers said XPoint development was progressing well while Micron engineers said it was meeting lots of problems. Our source wondered if Intel’s XPoint commercial management people knew of this, and whether messages were going upwards as they should.

This made them seriously doubt XPoint’s prospects. If this description of the situation is accurate it represents, in B&F‘s view, product development lunacy. The engineers/product managers were in a product development race but had to try to run while using crutches.

The industry consultant told us “Micron never liked 3DXP. It doesn’t solve any Micron issues, it is very complex to bring a new memory to market and Intel, Micron, Numonyx had been working on it for 20 years.

“Intel liked it for system reasons. Intel needs to get large amounts of memory, preferably non-volatile, to systems. This helps keep the storage component from slowing down compute. Two-level memory has been a plan from Intel for 10+ years. Intel can solve a lot of system problems with this.

“As a result of the above, Intel pushed Micron into doing 3DXP and come up with a Micron can’t lose finance model. Basically, Intel would pay for cost plus large overhead for bits shipped.”

“Micron wanted to convert the factory to DRAM/3D NAND … Intel said ‘No’, wanted to keep it for possible ramp up to support needs. Intel did a weird loan to IMFT to pay for upgrades and capital.

“Micron annexed the fab as allowed by agreement with the idea they could sell bits to Intel at a high price and still be able to sell SSDs. Intel’s ramp plans failed and they didn’t need the bits so they cancelled orders. Micron found the fast SSD business is not big enough. At this point, the two companies’ relationship was falling apart and they each blamed the other for financial issues.

“Intel had data embargoes, refused to let companies have samples, made them work at Intel sites, etc.”

He said “At one point, there were no Micron engineers working on 3DXP at all in development. Intel was supplying all the work at the Micron plant.”

The Intel spokesperson told us: “We aren’t going to comment on rumour or speculation.”

MIcron’s XPoint SSD-only restriction

Intel and Micron had, we’re told, a contractual agreement that Intel would sell both Optane SSDs and DIMMs but Micron could only sell SSDs. As we know, with hindsight, Micron never took advantage of this to properly push its own QuantX brand XPoint SSDs into the market.

The industry consultant said “Intel only strategically wanted DIMMs. The market for SSD was and is limited. DIMMs potentially could be a multi-billion dollar business. They had some agreements on where to focus and to allow Intel to drive the DIMM market. This limited Micron’s ability to see any large market. Again, the fast SSD market is very small and takes a lot of work. That’s why Micron gave up.

“The only ‘big win’ for Micron would be when the DIMM market took off, and Micron became second source and no one else could source it. Intels plans were that 50 per cent of the server boards had 3D XPoint. This never got above two per cent … and Micron couldn’t sell any SSDs, and Intel didn’t want any bits from Micron, so they took a huge underload charge on their part of the fab. At that point Micron realised there was no success ever for the market or fab.”

The spokesperson said: “We are not providing additional details about specific business agreements.”

Optane and 3D XPoint’s market success

This background conflict/stand-off between Intel and Micron, together with the need to add DRAM to Optane drives (possibly to overcome a write cooling problem), slowed Optane’s market penetration to the point where, today, its niche in the memory-storage hierarchy has shrunk to a very small size. Within that niche it is still important, but the question is if the niche is big enough to sustain a commercial Optane manufacturing and development operation.

We’d love to know if Intel offered the Optane business to SK hynix, along with its SSD operation, and if SK hynix declined.

An industry consultant we contacted, who wishes to remain anonymous, said “I have heard rumours that Intel offered it to SK hynix. The issue is that Intel wants to be all-controlling, so they said ‘you take it, we have all control, we have [right of first refusal] on all bits, you can’t license it… etc.’

“Hynix refused. Classic Intel: they think they have invented the greatest thing ever and try to control everyone. The end result is a lack of partnership, which kills them.”

In his view, “I have said the best option by far is for Intel to sell Optane to a Chinese company. Tsinghua, or another one who needs memory – let them throw capital at it. You can structure it so that the US government has no say in it. The issue is that Intel can’t control them and it will kill sales since China has political issues now.

“The end result is that the technology is a niche (big niche). Much slower than DRAM. much more expensive than NAND. It is not a game changer. Intel says it’s like when SSDs came out but the fact is that SSDs didn’t become ubiquitous until Samsung, Toshiba, etc sold them to everyone.”

Once more the Intel spokesperson said: “We aren’t going to comment on rumour or speculation.”

In the future we’ll no doubt get to read “spill the beans” stories about XPoint and Optane development. I for one can’t wait.