Analysis: Customers are sometimes faced with costly and sometimes unexpected permanent withdrawal fees when ending digital tape cartridge vaulting contracts. What lessons should be learned from this and how should organizations deal with multi-decade information retention?

For companies wanting to store physical media for long periods, Iron Mountain, for example, has long provided physical storage of boxed paper records in its vaults, initially inside the deep excavated caverns of an old iron ore mine, and subsequently in storage vault buildings around the globe.

Organizations with overflowing filed paper archives can send them offsite to Iron Mountain facilities for long-term storage, paying a yearly fee for the privilege. Extending this to storage of digital tape cartridges was a natural step for Iron Mountain.

But what happens if you want to end such a contract and remove your tapes? Well, there is a withdrawal fee. One customer claimed: “They are the Hotel California of offsite storage. You can check out your tapes any time you want – but you can never leave.”

“If you permanently take a tape out of Iron Mountain, they charge you a fee that is roughly five years of whatever revenue that tape would have made … So people just leave tapes there that they know have no purpose, because they can’t afford to take them out,” the source alleged.

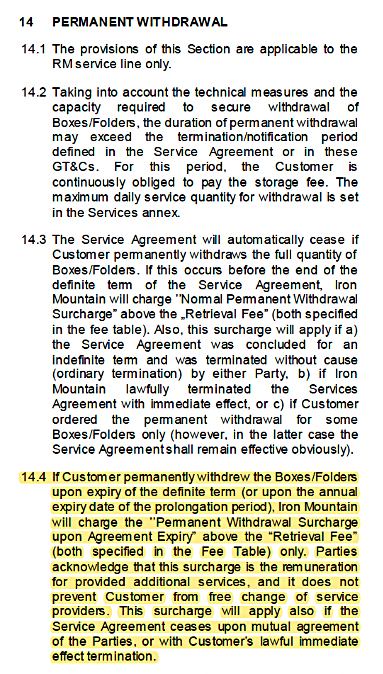

It happens that Iron Mountain charges a similar fee for permanent withdrawal if customers want to remove boxed paper files and store them in a cheaper facility or simply destroy them. This is stated in Iron Mountain’s customer contract’s Ts&Cs but can still be a surprise to some customers as it’s charged on top of a simple retrieval fee.

This led to the 2008 Berens and Tate lawsuit in Nebraska against Iron Mountain, in which the business tried to get the courts to rule that the permanent withdrawal fee was an unenforceable contract penalty provision. It lost its case.

A court document states: ”On August 12, 2004, Berens and Tate notified Iron Mountain that it wanted to remove all of its records from Iron Mountain and transfer those records to another storage company. Iron Mountain informed Berens and Tate that pursuant to the operative ‘Schedule A,’ Berens and Tate would be obligated to pay the ‘Permanent Withdrawal’ fee of $3.70 per cubic foot and a retrieval fee of $2.10 per cubic foot. According to Berens and Tate, the total charge to permanently remove its records would have been approximately $10,000.”

Iron Mountain told the court that the permanent withdrawal fee was necessary in order to compensate for the additional labor and services that are provided when large amounts of records are permanently removed. Because Berens and Tate had freely entered into the storage contract with Iron Mountain, the court decided the permanent withdrawal fee “was the parties’ agreed-upon compensation for services to be performed – specifically, the permanent removal of records.” Berens and Tate had to pay the fee.

Based on what we have been told, the vendor may be attaching a digital tape cartridge permanent removal fee along the same lines as its boxed paper record permanent removal fee. We sent an email to Iron Mountain on May 17 to check this but have heard nothing back despite sending follow-up requests for comment. If we hear back from Iron Mountain, we’ll add its reply to this story.

Our customer contact’s final thought was: “I’m sure it’s legal because it’s in the contract. But it’s wrong.”

It seems clear that prospective tape cartridge vaulting customers need to pay careful attention to all T&Cs and, if a permanent withdrawal fee is charged on top of a retrieval fee when ending the contract, be aware of this and be willing to pay it. The devil is often in the detail.

There are two questions that occur to us about this situation. One is how to deal with such contracts and the second, much bigger one, is how to obtain cost-effective and multi-decade information storage. Should that be on-site or off-site, and in what format?

Neuralytix

Neuralytix founding analyst Ben Woo said: “Of course any legal contract should be reviewed by a qualified attorney-at-law. But, to abandon long term tape storage providers on the basis of high retrieval costs would be a poor decision. Long term archive providers store backup tapes. Backup tapes by its very nature contain data that a customer hopes [it] will never see again, but is stored there for a small number of reasons – incremental forever backups, regulatory reasons, or (at least for the more recent tapes) disaster recovery.

“If a tape is required to be retrieved, the need must be extraordinary. VTL and technologies like these allow the customer to hopefully never rely on the tapes stored in storage.

“Whether the tapes need to be retrieved or whether a customer desires to combine older formats into newer ones require a lot of human effort, both of which carry costs.

“The only real alternative to tape is long term storage in the cloud – the problem with this is that customers will be paying for the storage of data irrespective of whether they use it or not for 10, 20, etc. years which quickly becomes cost-prohibitive and fiscally/economically irresponsible.”

Architecting IT

Architecting IT principal analyst Chris Evans said: “To summarise the problem, businesses use companies like Iron Mountain to create data landfill, rather than sending their content to a recycling centre. The Iron Mountain contract is constructed in such a way to make it more expensive to resolve the problem of the data landfill, than to simply add to it.”

“This is a massive topic. In my experience, tape has been used as a dumping ground for data that is typically backup media, where the assumption is the business ‘might’ need the data one day. In reality, 99 percent of the information held is probably inaccessible without specialist help.

“Setting aside the obvious concept of fully reading and understanding a contract before signing it, the long-term retention of data really comes down to one thing – future value. Most companies assume one or more of the following:

- We may need the data again in the future. E.g. legal claims, historic data restores.

- We might be able to derive value from the data.

- We have no idea what’s on our old media, so we better keep it “just in case”. (Most likely and the root cause of most problems)

“Storage costs decline year on year, for disk and tape. Generally, on a pure cost basis, it’s cheaper just to buy more storage and keep the data than to process it and determine whether it has value. So, businesses, which are an extension of humans and human behaviour, generally push the management process aside for ‘another day’, kicking the can down the road for someone else to solve in the future.

“The obvious technical answer to the problem is consolidation. … LTO-8 and LTO-9 are only 1 generation backward compatible. So, to recycle old media you will need old tape drives of no worse than 2 generations behind.

“[A] second problem is data formats. If you used a traditional data protection solution, then the data is in that format. Netbackup, for example, used the tar file format, storing data in fragments (blocks) of typically 2GB. Theoretically, you can read a tape and understand the format, but adding in encryption and compression can make this process impossible.

Specialists that can help make their money by having a suite of old technology (LTO drives, IBM 3490/3480, Jaguar etc) and tools that can unpick the data from the tape. However, none of these solutions restack. The restacking process would require updating the original metadata database that stores information on all backups, which is probably long gone. Even if it still exists, the software and O/S to run it will be hard to maintain and only adds to further costs. So stacking of old legacy data is pretty much impossible.

Data Retention Policy

Evans added: “The best way to look at the data landfill issue is with a business perspective. This means creating a data retention policy and model that helps understand ongoing costs. Part of the process is also to create a long-term database that keeps track of data formats, backup formats etc.

Imagine, for example, you created a data application in 2010, which stored customer data. In 2015 you migrated the live records to a new system and archived the old one. It’s 2024. Who within your organization can remember the name of the old application? Who can remember the server names (which could be tricky if they were virtual machines)? Who can remember the data formats, the database structures? Was any of that data retained? If not, the archive/backup images are effectively useless as no one can interpret them.

“So, businesses need to have data librarians whose job is to log, track, audit and index data over the long term.

“My strategy would be as follows:

Fix Forward – get your house in order, create data librarians and data retention policies if they’re not already in place. Work with the technical folks to actively expire data when it reaches end of life. Work with the technical folks to build a pro-active refresh policy that retires old media and moves data to newer media. If you change data protection platform, create a plan to sunset legacy systems, running them down over time.

For example, if your oldest data is 10 years, then you’ll be keeping some type of system to access that data for at least 10 years. Look at storing data in more flexible platforms. For example, using cloud (S3) as the long-term archive for backup/archive data makes that content easier to manage than tape. It also makes costs more transparent – you pay for what you keep until you don’t keep it any longer.

Remediate Backward – Create a process to remediate legacy data/media. Agree a budget and timescale (for example, to eliminate all legacy content in 10 years). Triage the media. Identify data that can be discarded immediately, the data that must be retained and the data that can’t be easily identified. Create a plan to wind each of these down.

“…The exact strategy is determined by the details of the contract. For example, say the current contract is slot/item based and is $1/item per year. If you have 10,000 tapes, then reducing that by 1,000 items per year should eliminate the archive in 10 years. If the penalty is determined by the last year’s bill, then (theoretically) the final bill might be 5x times $1,000 = $5,000 rather than $1,000, but significantly better than the $10,000/year being paid in year 1. This is speculation of course, because it depends on the specifics of the contract. I’d have a specialist read it and provide some remediation strategy, based on minimizing ongoing costs.

“Most businesses don’t want to solve the legacy data sprawl problem because it represents spending money for no perceived value. This is why Fix Forward is so important, as it establishes data management as part of normal IT business costs.

“The opposite side of the coin to costs is risk. Are your tapes encrypted and if not, what would happen if they were stolen/lost? What happens if you’re the subject of a legal discovery process? You may be forced to prove that no data exists on old media. That could be very costly. Or, if you can’t produce data that was known to be on media, then the regulatory fine could be significant.

“So, the justification for solving the data landfill can be mitigated by looking at the risk profile,” Evans told B&F.