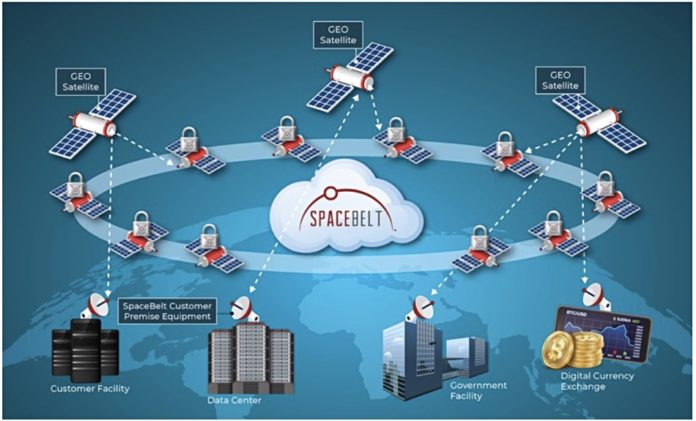

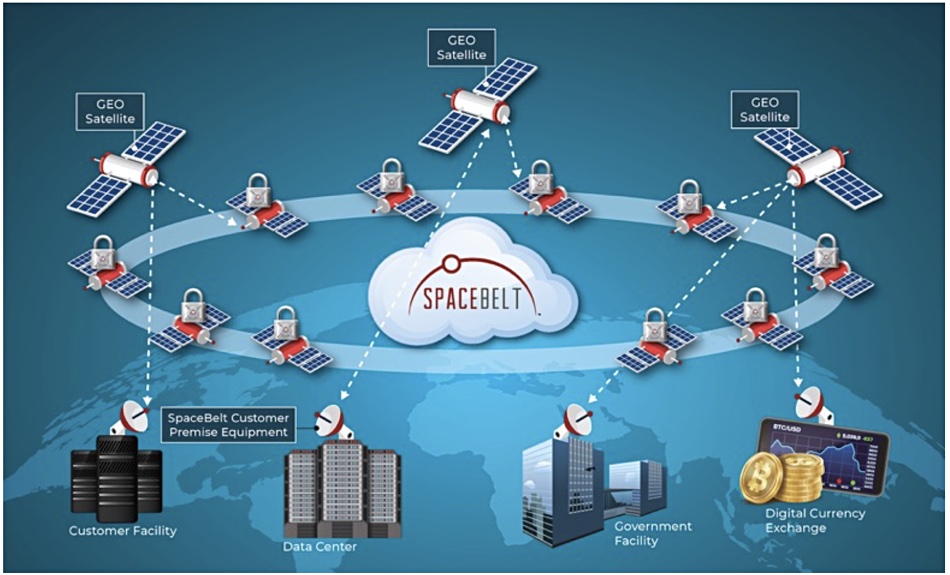

Cloud Constellation Corporation is building Spacebelt, a data storage service using low Earth orbit (LEO) satellites that is claimed to be more secure than any data vault on Earth.

The satellites are to form a patented high speed global cloud storage network of space-based data centres continuously interconnected with their own dedicated telecom backbone for high-value and highly sensitive data assets.

Spacebelt’s satellite storage and transmission network sidesteps worldwide jurisdictional restrictions and laws regarding how data is moved between countries. Using its private network and ultra-secure dedicated terminals, the system bypasses leaky internet and leased lines, CCC says.

A short April 14 announcement connecting IBM with Spacebelt prompted Blocks & Files to take a look at Cloud Constellation Corp. and its plans.

In the announcement, CCC said IBM had been given the results of a benchmarking test for VGG-13 Model Machine Learning applications hosted on Spacebelt’s satellite hardware. This was claimed to show “it’s a scalable, secure platform for highly secure services and mission-specific ML applications for commercial, government and military organizations.”

Cloud Constellation Corporation joined IBM’s PartnerWorld program in May 2018 to collaborate on cloud services based on IBM’s blockchain technology. It said it has a roadmap to support a portfolio of IBM cloud services on a SpaceBelt OpenShift cloud infrastructure, but no further details are available at time of publication.

Cloud Constellation Corporation

CCC was founded in 2015 and is based in Los Angeles. The company claimed at the time that using a satellite network for cloud storage would greatly reduce carbon emissions and energy bills.

CCC bagged a $5m A-round in 2016 and said in December 2018 it was arranging a $100m investment from the Hong Kong-based HCH Group, as part of a $200m B-round of funding. It said Spacebelt needed $480m to get the satellites into orbit and the system working.

However, in November 2019 the company said that the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) had identified difficulties centred on the HCH Group being a Chinese company. CCC said at the time it was talking with three other sources of funding, but has announced no further funding details.

Spacebelt hardware

The planned hardware is a ring of 10 low Earth orbit (LEO) satellites in a 650-kilometre equatorial orbit. They will be accessed from ground level via geostationary satellites orbiting 36,000 kilometres above the Earth.

LeoStella, a joint venture of Thales Alenia Space and Spaceflight Industries, will build the satellites, which are planned to be operational with CCC’s first DSaaS in the second 2022 quarter.

Accessing points on Earth must have a ground station with a very small aperture terminal (VSAT) that can link to these geostationary satellites. Then there is a network hop to the Spacebelt ring.

The Spacebelt satellites will be connected with redundant and self-healing photonic (laser) rings in a Layer 3 topology.

The number of satellites in this ring has risen and fallen as CCC has worked to develop Spacebelt technology and economics. Back in 2016 it said there would be 16 satellites in the belt. This dropped to 12 in September 2017, 8 in December 2018 and then rose to 10 in January this year.

That number could grow – CCC has said it will add satellites to the constellation for service scaling, new services, and new technology.

In 2017 it signed a deal with Virgin Orbit as launch partner for the 12 satellites then planned. Virgin Orbit had planned an air-launched rocket, containing a small satellite, released from a Boeing 747 flying at 35,000 feet. This obviates the need for a ground launch with a thumping big first stage rocket. Also the satellite launch process does not need the typical expensive space flight ground installation. There would be 12 individual missions with the first launch scheduled for 2019. That launch did not take place.

CCC is now considering an Arianespace Vega C rocket which could launch 10 satellites in a single mission, as an alternative to Virgin Orbit. The per satellite launch cost could be cheaper than the multiple launch Virgin Orbit scheme.

3-node space-based data vault

Only three satellites in Spacebelt’s ring are data stores, and data is replicated between them for redundancy. The other seven satellites are involved in relaying data.

The Spacebelt satellites are not geostationary, which means that they move in orbit above any ground station. The Spacebelt system has to work out which satellite is above a particular ground station. Then it has to organise data transmission to and from the three data storage satellites around the ring across the relay satellite network in order to reach the ground station.

Spacebelt’s storage capacity has changed from an initial 12 petabytes in February 2018 to 5PB in December 2018. Dennis Gatens, CCC chief commercial officer, told us in an email interview last week: “Our design has evolved where we will initially have 1.6 PB distributed across the 10 satellite constellation.”

Storage medium

In essence CCC is offering to store data in a three-node distributed data centre. The nodes happen to be in orbit. How fast you can get data in and out seems a basic question as is inquiring if the access protocol is block, file (NFS or SMB) or object (S3).

We understand that VSAT data rates range from 4 Kbit/s up to 16 Mbit/s. In IT data communications terms this is slow. We think this implies it will be a file transfer protocol; either NFS or SMB, rather than block.

Gatens said the data storage medium used in the satellites is a “closely held design detail”, as are the read and write IO rates and access protocols.

From the Blocks & Files point of view the basic answer is surely flash, hardened to withstand the solar radiation levels found in orbit. Disk drives are likely to break and are unfixable – unless a techie is rocketed into orbit to replace them.

Technology ageing

An aspect of the service is that the storage technology will be fixed for the operational life of the satellites. If that life is 10 years then the technology will be 10 years old at the satellite’s end-of-life.

It’s not really conceivable that a ground-based data storage facility would use the same storage technology for 10 years. That would be like using NAND flash from the year 2010 today, which would seem slow and expensive. It also means that the storage satellites would need to have sufficient over-provisioning to cope with their flash stores having a 10-year operational life.

A typical enterprise SSD has a 5-year warranty and is over-provisioned to support that.

To overcome this disadvantage Spacebelt has to offer pretty compelling benefits. CCC’s pitch is security and claimed fast data transmission speed.

Spacebelt users will be able to transport and store large blocks of data quickly and securely it claims, and without exposure to terrestrial communications infrastructure. This will protect their critical data from unauthorised access and also provide global communications with lower latency than today’s multi-hop networks.

Cloud Constellation’s marketing message is: “SpaceBelt DSaaS serves as a key market differentiator for our global partners, offering the ultimate air gap security to their enterprise customers reliant on moving highly sensitive, high value and mission-critical data around the world each day. Cloud Constellation’s mission is to insure our customers data is securely stored while providing robust, secure global connectivity.”

So, Spacebelt is both a secure data vault and high-speed data mover using its own private network. How is this more secure than a ground-based 3-node data vault?

Air-gapping

CCC said Spacebelt is air-gapped and therefore secure. Blocks & Files understands air-gapping to mean no network connectivity – as is the case with offline tape cartridges. We asked Gatens how CCC can say Spacebelt data storage is air-gapped when the satellites are permanently online.

Gatens replied: “We refer to the air gap concept as there is no connection to our network that is not installed and controlled by our operations, and each end point is located within our enterprise customer’s facilities and is directly attached to their network. There is no terrestrial network connectivity to SpaceBelt for users or network management.”

He is saying it’s all effectively private. An end-user customer’s own network connects to Spacebelt’s network via geostationary satellites acting as transponders that hook up to the Spacebelt ring. That means ransomware could in theory attack data held in Spacebelt – unless there is some barrier to that happening.

CCC needs to build a ground-based version of its 3-node data store, accessible through always-on VSAT connections and then prove to a satisfactory level that ransomware can’t attack the data in it.