Michael Tso, co-founder and CEO of object storage supplier Cloudian, thinks the rush to the public cloud is slowing.

The on-premises world has caught up with the public cloud as it now features consumption-based business models, elasticity from software-defined storage, and agile development (containers.)

That means that the gulf between the two has narrowed which in turn reduces the cost benefits of the public cloud.

Or so says Tso, who told Blocks and Files in an interview that cloud data repatriation and edge data growth are great drivers for the company. Repatriation enables workloads to return “home”. And cloud is too slow and costly for bulk transmission of edge data.

Who says so? I say, Tso

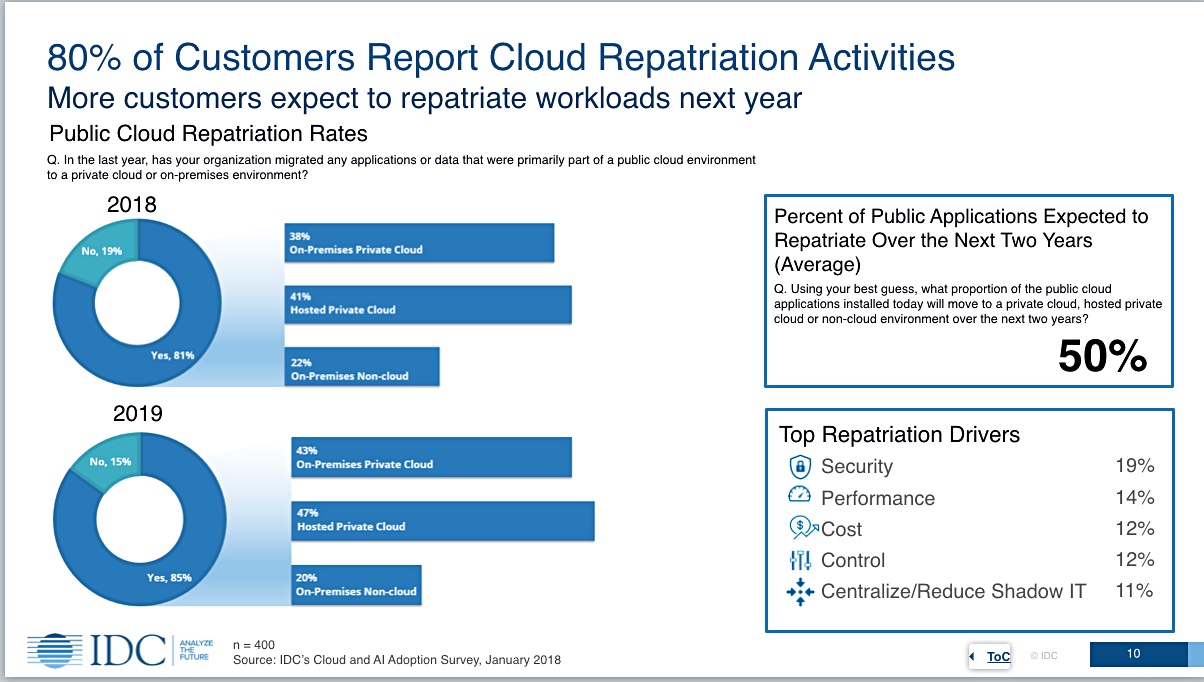

According to Tso, the idea that workloads and data, once migrated to the public cloud, will stay there forever is wrong. As evidence, he cites an IDC report, Cloud and AI Adoption Survey, which was published in the summer of 2018.

The report authors found 80 per cent of customers repatriating workloads from public cloud environments. Some 85 per cent are expected to repatriate data next year.

On average, survey respondents expect to move 50 per cent of their public cloud applications to hosted private or on-premises locations over the next two years.

Workload repatriation rates are not consistent across different types of business and business functions. The IDC researchers say younger organisations are significantly more likely to repatriate public cloud workloads than those in business for more than 25 years.

Companies that are self-described market disrupters, market makers, under reinvention or transitioning have the highest rates of repatriation.

Two-way street

Interestingly, companies deploying “true hybrid cloud capabilities” have some of the lowest rates of repatriation. These businesses have the ability to run a single application across multiple cloud environments and hence do not need to move workloads at the same rate as organisations without such automation.

On the other hand, companies reporting high levels of application interdependencies are the most likely to repatriate workloads, probably due to a need to connect to on-premises data or applications,

Kinda obvious, but repatriation rates rise when public cloud costs are perceived to be higher than other computing costs. Ccosts are more likely to be visible to the IT organisation, which is most likely to repatriate applications and data from public cloud environments.

Correspondingly, line of business decision makers are the least likely to repatriate workloads.

Hey, you, get my data off of your cloud

Repatriation accounts for some on-premises data growth but machine-sourced unstructured data accounts for the lion’s share, according to Tso. This is growing exponentially, and on-premises data storage requirements will grow in lock-step.

On-premises data growth is helped along by “semiconductor source systems getting higher resolution every year,” such as surveillance cameras taking higher resolution videos. Cloudian is also finding customers with machine-generated data, such as DNA genomics, CAT scans, MPI, surveillance and IoT sensors/systems, are all receptive to these messages.

Data gravity is another factor affecting on-premises data storage; the cost and ease of moving it, and this affects repatriated data as well. (Find out more about data gravity in this Register article.)

Storage drive density is growing exponentially but moving data to the cloud is getting harder because “cable capacity does not grow exponentially,” Tso argues.

The upshot is that data will continue to grow at the edge of the network “because it can’t move. … data gravity is huge. It takes years to lay cables.”

If sending 2PB today across network links to the public cloud is unaffordable then sending 5PB in 12 months time will be even more unaffordable, and 10-15PB, a year later? Impossible.

Back for good?

Once the data is back on-premises (or private cloud) will it return to the public cloud?

Tso thinks it unlikely, because the data keeps growing and the cost of network transmission to the cloud will be prohibitive

He said: “We’re seeing the pendulum swing back.” In an aside he mentioned a US customer using the internet for group interactions, in which data was stored in the Amazon cloud. Citing GDPR concerns and data sovereignty issues, the company repatriated to store the data on a dozen Cloudian systems for different countries.

Tso said existing customers account for about 40 per cent of Cloudian sales and their expanding requirements are driving revenues. This of course fits in nicely with his data repatriation and edge data growth thesis. These trends if confirmed will greatly benefit Cloudian and other cloud-like unstructured data storage vendors.