Hyve Solutions sells storage hardware to its hyperscaler customers, but not software — because they don’t want it. What, then, do hyperscalers want?

Hyve is a TD Synnex business unit that sells, delivers and deploys IT Infrastructure — compute, networking and storage — to hyperscaler customers. That means the likes of AWS, Azure, Facebook, Twitter, etc., though it would not confirm any as customers. Typically the hardware is rackscale and complies with Open Compute Project standards. Hyve also sells into IoT and edge deployments — such as ones using 5G, where sub-rackscale systems may be typical and site numbers can be in the hundreds.

We were briefed by Jayarama (Jay) Shenoy, Hyve’s VP of technology and our conversation ranged from drive and rack connection protocols to SSD formats.

Shenoy said Hyve is an Original Design Manufacturer (ODM), and focusses exclusively on hyperscaler customers and hardware. It doesn’t really have separate storage products — SANs and filers for example — with their different software. Separate, that is, from servers.

Shenoy said “We make boxes, often to requirements and specifications of our hyperscale customers. And we have very little to do with the software part of it.”

Storage and storage servers

Initially hyperscalers used generic servers for everything. “A storage server was different from a compute server only in the number of either disks or SSDs. … There really was not that much different at times about the hardware, being storage. That is changing now. But the change will manifest in, I would say, two or three years. Things move much more slowly than we would like them to move.”

One of the first big changes in the storage area was a drive type change. “So the first thing that happened was hard drives gave way to SSDs. And initially, for for several years, SSDs was a test. By now that trend is really, really entrenched so that, you may just assume that the standard storage device is an SSD.”

As a consequence, there was a drive connection protocol change. “In the last three years, SATA started giving way to NVMe, to the point where now, SATA SSD would be a novelty. … We still have some legacy, things that we keep shipping. But in new designs, it’s almost all NVMe.”

Shenoy moved on to drive formats. “Three years ago, hyperscalers were sort of sort of divided between U.2 [2.5-inch] and M.2 [gumstick card format]. All the M.2 people kind of had buyer’s regret. … All three of them have confirmed that they’ve moved or are moving to the E1.S form factor.”

E1.S is the M.2 replacement design in the EDSFF (Enterprise and Datacentre SSD Form Factor) ruler set of new SSD form factors.

Shenoy said “There are primarily three, thank goodness. The whole form factor discussion settled out. That happened maybe a year and a half ago, when Samsung finally gave up on its NF1 and moved to EDSFF.”

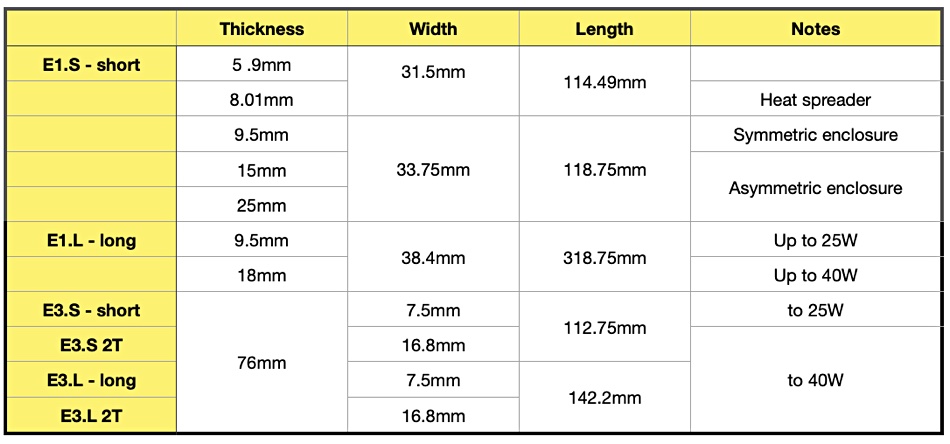

There are two basic EDSFF formats: E1 and E3. Each comes in short and long sub-formats, and also with varying thicknesses:

The E3 form factor allows for x4, x8, or x16 PCIe host interface. Shenoy’s basic threesome are E1.S, E1.L and E3.

Shenoy told Blocks and Files “At a high enough level, what seems to me to be happening is E3 is going into … what would have been known. What is still known, as enterprise storage with features like dual porting. … E1 does not really support dual porting.”

Hyperscalers have adopted the E1 format, “but to this date, I have not come across a single one that has an E3 [drive].” He explained that “the people who picked U.2 are happy with U.2 and are going to like U.3 instead of E3.”

The difference for hyperscalers between E1.S and the E1.l format is capacity. “[With] E1.S versus E1.L the difference is exactly one capacity point, meaning the highest capacity point in the SSD line. … Only the highest capacity port will be offered in E1.L. And everything else will be offered in E1.S. So even .L is basically restricted to whoever is going to be today adopting the 30 terabyte drive capacity point.”

Edge computing

“In terms of hardware, there’s one other subtle, subtle change — well, actually, not so subtle — that’s been happening in hyperscale. When we think of hyperscale, we think of big datacentres, hundreds of thousands of nodes, and racks, and racks, and racks and racks. But edge computing … has stopped being a buzzword and started to be very much been a reality for us in the last couple of years.

“The way edge computing changes storage requirements is that hotswap of SSDs has come back. Hotswap — or at least easy field servicing — has come back as a definite requirement.” Shenoy thinks that “Edge computing driving different form factors of servers is a given.”

Another change is disaggregation. Shenoy said “The larger hyperscalers have basically embraced network storage. So it’s basically object storage or object-like storage for the petabytes or exabytes of data [and] that’s placed on hard disks. And SSD is a fast storage. It’s a combination of either — it can be object storage, or sometimes it has to be even block storage.”

PCIe matters

What about the connection protocols in Hyve’s hyperscaler world? For them, “Outside of the rack … can do anything as long as it’s Ethernet. Within the rack, there’s much more leeway in what cables people will tolerate, and what exceptions people are willing to make.” Consider hyperscale storage chassis as basically boxes of flash or disks — JBOFs or JBODs. As often as not they’ll be connected with a fat PCIe cable. In Shenoy’s view, “PCIe within a rack and Ethernet outside of a rack, I think is already a sort of a thing or reality.”

What about PCIe generation transitions — from gen 3 to 4 and from 4 to 5? Shenoy said there are very few gen 4 endpoints as yet, especially GPUs, which “were almost ready before the server CPUs. … It’s partly the success of AMD, as Rome had to do with being the first with PCIe 4.” In fact the “PCIe gen 4 transition happened rather quickly. As soon as the server CPUs were there, at least some of the endpoints were there. SSDs took a little bit of time to transition to gen 4.”

But PCIe 5 is different: “Gen 5 …. and the protocol that writes on top of gen 5, CXL, is turning out to be … very different. It’s turning out to be like the gen 2 to gen 3 transition, where the CPU showed up and nobody else does.”

According to Shenoy “The gen 5 network adapters are also lacking actually … to the point where the first CPU to carry gen 5 will probably go for, I don’t know, a good part of a year without actually attaching to gen 5 devices. That’s a long time.”

Shenoy was keen in this point. “The gen 5 transition is kind of looking a little bit like the gen 3 transition. … Gen 3 stayed around for a really, really long time.”

Chassis and racks

Hyve has standard server and storage chassis building blocks. “We have our standard building blocks. And then we have three levels of customisation. … So chassis is one of the things that we customise pretty frequently.” Edge computing systems vary from racks to sub-racks. The edge computing racks may be sparser — Shenoy’s term — than datacentre racks. Every one, without exception, will contain individual servers and may also contain routers and even long haul connection devices.

They are more like converged systems than Hyve’s normal datacentre racks.

Customer count

How has Hyve’s hyperscaler customer count changed over the years? Shenoy said “The number of hyperscalers has gone up, or the number of Hyve customers has gone up slightly, I would say, in the last three years.

“The core hyperscale market has not changed. Three years ago, or five years ago, you had the big four in the US — big five if you count Apple — and then the big three in China. And then there was a bunch of what Intel calls the next wave” — that means companies like eBay and Twitter. “These would have been known ten years ago as CDNs. Today it would be some flavour of edge computing. I am making reference to them without [saying] whether they are our customers or not.”

He said “Then the other type of customers that have come into our view … are 5G telcos.”

That means that the addressable market for Hyve in terms of customer count three to five years ago was around ten, and is now larger than that — possibly in the 15 to 20 range. It is a specialised market, but its buying power and its design influence — witness OCP — is immense.

That design influence is affecting drive formats — witness the EDSFF standards set to replace M.2 and 2.5-inch SSD form factors. Nearline high-capacity disk drives will stay on in their legacy 3.5-inch drive bays. The main point of developing EDSFF was to get more SSD capacity into server chassis while overcoming the consequent power and cooling needs.

Mainstream enterprise storage buyers will probably not come into contact with Hyve, unless they start rolling out high numbers of edge sites using 5G connectivity. Apart from that, Hyve should remain a specialised hyperscale IT infrastructure supplier.

Bootnote: Distributor Synnex became involved in this whole area when it started supplying IT infrastructure to Facebook. That prompted it to form its Hyve business ten years ago. The rise of OCP and its adoption by hyperscalers propelled Hyve’s business upwards.

The TD part of the name comes from Synnex merging with Tech Data in September last year, with combined annual revenues reaching almost $60 billion. This made it the IT industry’s largest distributor.