What is a startup? What do you call a startup that refuses to grow up and have an IPO — a Peter Pan?

Is Nebulon, a four-year-old company that has raised $14.8 million in a single VC round a startup? Obviously, yes.

Is VAST Data, a six-year-old company that has raised $263 million in four funding events, a startup? We’ll say yes.

Is Fungible, a seven-year-old company that has raised $310.9 million in three rounds a startup? We’ll say yes, again.

Is Databricks, a nine-year-old VC-funded company that has raised $3.6 billion in eight funding events, a startup? The VCs clearly expect a great exit and don’t see this company as a never-to-grow-up Peter Pan.

What of Cloudian, an eleven year-old company that has raised $173 million in six funding events? Still a startup? Well, it’s not so clear, and we’d probably say not.

And how about Delphix, a fourteen-year-old company that has raised $124 million in four funding events. Do we still call it a startup? Fourteen years is a long time to be in startup mode.

Are fifteen-year-old Egnyte and Scale Computing, with $137.5 million and $104 million raised respectively, startups? The founders are still in control. Both say they are growing. Both are VC-funded. And yet to call them startups just seems wrong — their starting-up phase is surely over.

The classic startup in the storage space is a venture capital-funded enterprise growing at a faster-than-market rate through technology development and demo, prototype product build, first product ship, to general availability and market acceptance, followed by an IPO or an acquisition.

Startup-to-IPO journey

Let’s look at three classic startup-to-IPO stories.

All-flash array supplier Pure Storage raised $470 million over six rounds and took seven years from founding to IPO. Six years later it is still going for growth over profitability and making losses.

Hyperconverged Infrastructure (HCI) vendor Nutanix took eight years and five funding events, raising $312.6 million, to reach its IPO. It’s still loss-making five years after IPO as it keeps on prioritising growth over profitability.

It took Snowflake nine years from founding to run its IPO. That effort needed seven funding rounds and $1.4 billion in raised capital.

The overall picture is eight years from startup to IPO. This is startup success. This, or being acquired — especially being acquired in a bidding war, as Data Domain. Acquisitions like this are successful but other acquisitions can be made at a discount to raised capital because the acquiree had not reached escape velocity and was a semi-successful (Actifio) or semi-failing (Datrium) company.

Escape Velocity

We can view venture capital as the rocket fuel needed to enable a startup to reach escape velocity and become a self-sustaining — meaning ultimately profitable — business.

Some startups clearly fail to reach escape velocity, such as Coho Data, which closed down six years after being founded and raising $65 million. Ditto Data Gravity, which closed down in 2018 six years after startup with $92 million raised.

A semi-success or semi-failure was Datrium, which was bought by VMware nine years after its founding with $165 million raised. Tegile was another similar company, bought by Western Digital with $178 million raised nine years after being founded

Other startups fail or semi-fail and get bought by private equity, which aims to extract value from the ruins and then sell it off. Thus PE-owned StorCentric bought seven-year-old Vexata, into which VC backers had ploughed $54 million.

Veeam was bought for $5 billion by private equity, but this was not a failure — it was a signal of its success, and an outlier.

And what of the rest? Older, VC-funded startups, such as Cloudian, Databricks and Delphix, that have not reached escape velocity?

The in-betweeners

Such companies are no longer operating in startup mode, surely? You can’t sustain that sense of developing completely new technology to change the world for nine, eleven or fourteen years. The backing VCs might still hope for a profitable exit — they surely do with Databricks. Yet these post-puberty companies, if you will forgive the expression, these near-teen and teenage companies, are in-between the startup phase and whatever their exit phase from VC funding will be.

HPEer Neil Fleming, tweeting personally, wrote: “Can we talk about what defines a startup? Databricks is eight years old, has 2K employees and turn over of $425Mm (according to Wikipedia). What’s the threshold of when something stops being a startup and starts being a business?”

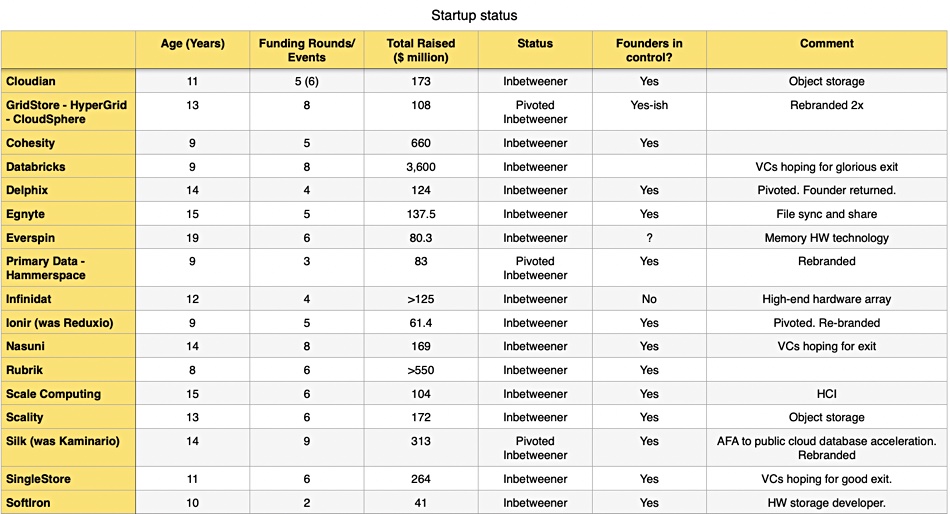

Storage consultant Chris Evans identifies Peter Pan companies as the ones that never grow up. We listed pre-IPO, pre-acquisition, post-startup storage companies that could be classed as “in-betweeners” in a table, showing their age, number of funding events, and total raised:

They are all nine or more years old, with Everspin topping this characteristic at 19 years of age. The in-between stage can clearly be a long march.

Pivots

Some of them are marked as having pivoted — meaning that they changed the marketing direction of their technology. Thus Kaminario started out as an all-flash array hardware vendor, pivoted to being an all-flash array software vendor and then pivoted again, with a rebrand to Silk, and focussed its software technology on accelerating databases in the public cloud. It is fourteen years old and still has its founding CEO in charge. He’s managed to raise $313 million in nine rounds and the VCs are still, it appears, hoping for a successful exit. Similarly, GridStore became HyperGrid, which became CloudSphere. Reduxio has become Ionir, and Primary Data evolved into Hammerspace. These companies may prefer to say that their new enterprises are fresh startups, but we can see a technology trail and a founding team link between the old and new companies.

The oldest inbetweener we have in the table is Everspin. ExaGrid is 18 years old and still hoping for an IPO. HCI vendor Pivot3 was bought by Quantum 19 years after it started up, passing through 11 eleven funding events which raised $247 million. That was not a successful exit.

Nantero, developing carbon nanotube memory, is 20 years old, with $120 million funding accumulated through eight funding events.

One of the longest-lived in-betweeners is HPC storage vendor Panasas, at 21 years, and $155 million raised in, we think, eight rounds. It may well be profitable. We should note that DataCore, although older, at 23 years old, is an outlier. It had not been a VC-backed startup for many years until it took in $30 million in 2008. The company has been profitable for ten years and very recently bought Maya Data.

It is ridiculous, we would assert, to view DataCore, Everspin, Nantero and Panasas as startups.

We think a better term is in-betweener, until a better one comes along at any rate. We won’t refer to any company more than nine years old – the Snowflake startup-to-IPO period – as a startup any more.